A failing blower resistor and a failing blower motor can look similar, but the pattern of speed control is the quickest separator: resistors usually lose specific lower speeds, while motors usually struggle across multiple speeds or make noise and draw excess current. Next, you’ll confirm with simple, low-risk checks—fuse/relay behavior, connector heat, voltage at the motor, and whether “high speed” bypasses the resistor path.

Besides identifying the correct part, a good diagnosis also prevents repeat failures, because a resistor can burn out from poor airflow, melted connectors, or an over-amping motor. To start, you’ll use symptom logic (speed map, noise, smell, intermittent operation) to narrow the suspect system before touching a multimeter.

Beyond that, HVAC airflow restrictions can mislead you: a clogged cabin filter or debris in the blower housing reduces airflow, increases heat at the resistor pack, and can make a healthy motor feel weak. So you’ll pair electrical checks with airflow checks to avoid replacing the wrong component.

Finally, “Giới thiệu ý mới”: you’ll follow a step-by-step path that begins with what you can observe from the driver’s seat, then moves to targeted measurements, and ends with decision rules that tell you whether the resistor, motor, wiring, or control signal is the true root cause.

Is it the blower resistor or blower motor when some fan speeds don’t work?

Most often, missing one or more lower fan speeds points to the blower resistor, while a blower that only works on “high” is a classic resistor-path failure. Next, you’ll confirm the speed pattern and use a quick “high-speed bypass” logic before doing any deeper electrical work.

To begin, map the symptom precisely: which speeds work, which don’t, and whether the blower cuts in/out when you wiggle the connector or tap under the dash.

Why does a bad resistor usually kills only certain speeds?

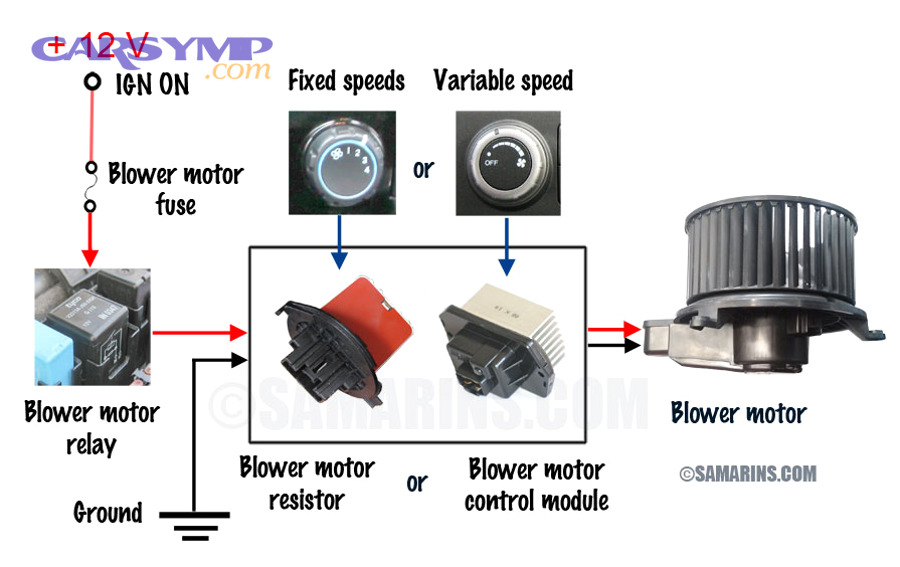

A resistor pack “drops” voltage for lower speeds and is bypassed on high, so a burnt resistor element can remove one or multiple lower settings while leaving high intact. Next, you’ll use this bypass behavior as a quick comparison rule when you test power at the motor.

Specifically, many systems route high speed through a relay and a separate circuit path, while the lower speeds route through resistor coils or a solid-state module that reduces voltage. When a coil opens, the corresponding speed becomes dead, but the motor still runs when the circuit bypasses that element.

In practice, you’ll see patterns like: Speed 4 works, speeds 1–3 dead; or speeds 1–2 dead, 3–4 okay. That pattern is more “resistor-shaped” than “motor-shaped.”

When missing speeds can still be a motor problem?

Yes, it can be the motor if the motor is intermittently open, has worn brushes, or the connector overheats and drops voltage under load, making some speeds appear dead. Next, you’ll check for voltage drop and heat at connectors to avoid mislabeling a wiring issue as a resistor issue.

For example, if the blower sometimes runs at any speed after you hit a bump, tap the housing, or cycle the switch repeatedly, worn brushes or a failing commutator can mimic a “dead resistor.” Also, if the connector is melted, the circuit may fail under the higher current of high speed even if lower speeds sometimes operate.

What does “only works on high” strongly imply?

“Only works on high” strongly implies the resistor path (or its connector/relay) is open, because high usually bypasses resistors and feeds the motor more directly. Next, you’ll verify by measuring motor voltage on high versus a lower speed to see whether the motor is being commanded but not supplied through the resistor circuit.

If you have 12–14V at the motor on high and near-zero or unstable voltage at lower settings, the resistor/module or its connector is the prime suspect. If voltage is present but the motor doesn’t spin, the motor becomes the suspect.

How can you diagnose blower resistor vs motor from the driver’s seat?

You can diagnose quickly by comparing speed response, noise, smell/heat, and intermittent behavior: resistors correlate with “missing steps,” while motors correlate with “weak airflow + noise + vibration” or cutting out under load. Next, you’ll turn those observations into a simple decision tree before opening any panels.

To start, run the blower through every speed with the engine running (stable voltage) and note: does the blower ramp smoothly, do some steps do nothing, or does it surge and fade?

What symptom patterns point to a resistor failure?

Resistor failure is most consistent with “one or more lower speeds dead,” “fan works only on high,” or “fan runs but speeds don’t change correctly.” Next, you’ll look for heat damage at the resistor connector because it often fails together with the resistor pack.

Specifically, you may notice that speed 1 is dead, speed 2 weak, speed 3 normal, speed 4 strong—or speeds 1–3 dead and only speed 4 works. That staircase pattern matches how resistor stages are built.

Another clue is a burning-plastic smell near the passenger footwell right after you select a lower speed. That can indicate resistor overheating or connector resistance creating heat.

What symptom patterns point to a motor failure?

Motor failure is more consistent with squealing, chirping, grinding, vibration, or airflow that’s weak on every speed even though you can hear the motor strain. Next, you’ll link noise and airflow quality to bearing wear, debris contact, or brush failure.

Common motor-shaped symptoms include: a high-pitched squeal at startup (dry bearing), a scraping sound (leaves/foam contacting the squirrel cage), or a rumbling vibration felt in the dash. If the blower sometimes starts only after tapping the housing, worn brushes are likely.

Also note: if airflow is weak but motor speed audibly changes with the switch, your problem may be airflow restriction (filter/debris/door) rather than resistor or motor electrical failure. That’s why you’ll pair “sound” with “airflow volume.”

How do intermittent issues change the diagnosis?

Intermittent operation can be resistor, motor, relay, or connector, but “starts when tapped” leans motor, while “cuts out when connector is touched” leans wiring/connector heat damage. Next, you’ll do a gentle harness wiggle test and then confirm with voltage-drop checks rather than guessing.

When electrical contacts are failing, the blower may run for minutes, then stop, then resume when the connector cools. Melted connectors often show as discoloration, brittle plastic, or a loose pin fit. A failing motor can also be thermal: as it heats, internal resistance changes and brushes lose contact, causing cut-outs.

What electrical tests separate a bad blower motor from a bad resistor?

Measure voltage and ground at the motor while commanding different speeds: if the motor receives proper voltage on a given speed but doesn’t spin, the motor is bad; if voltage is missing only on certain speeds, the resistor/module or control path is bad. Next, you’ll prioritize safe, accessible tests that don’t require cutting wires.

To begin, access the blower motor connector (often passenger footwell) and the resistor/module connector (often mounted in the air duct). Use back-probing or a proper test lead, and keep hands clear of the fan cage.

How to do the “motor feed test” without guessing?

Command the blower to high and measure motor supply voltage: if you see near battery voltage and the motor doesn’t run, suspect the motor; if voltage is low, suspect wiring, relay, or ground. Next, you’ll repeat on a lower speed to see whether voltage changes appropriately through the resistor path.

On high, many systems should deliver roughly 12–14V at the motor (engine running). If you see 12–14V and a solid ground but no rotation, the motor or mechanical obstruction is likely.

Then move to speed 1 or 2. A resistor-based system should show reduced voltage at the motor (often significantly lower than battery voltage). If it stays at 0V on low but is normal on high, that strongly points to the resistor/module circuit being open.

How to use voltage drop to catch melted connectors and bad grounds?

Voltage drop testing finds hidden resistance: high drop across a connector or ground indicates heat and loss under load, which can mimic resistor or motor failure. Next, you’ll test the positive side and ground side separately while the blower is commanded on high.

To check the positive side, measure from battery positive to the motor positive terminal while the blower runs. A large reading indicates voltage is being “lost” in the supply path (connector, relay, fuse link, wiring). To check the ground side, measure from motor ground to battery negative while running; a large reading indicates ground path resistance.

Heat is the physical hint: if a connector is warm/hot after a short run, its resistance is likely high. Replace damaged connectors when replacing the resistor pack, because the failure often repeats if the connection remains poor.

What resistance/continuity tests matter for the resistor pack?

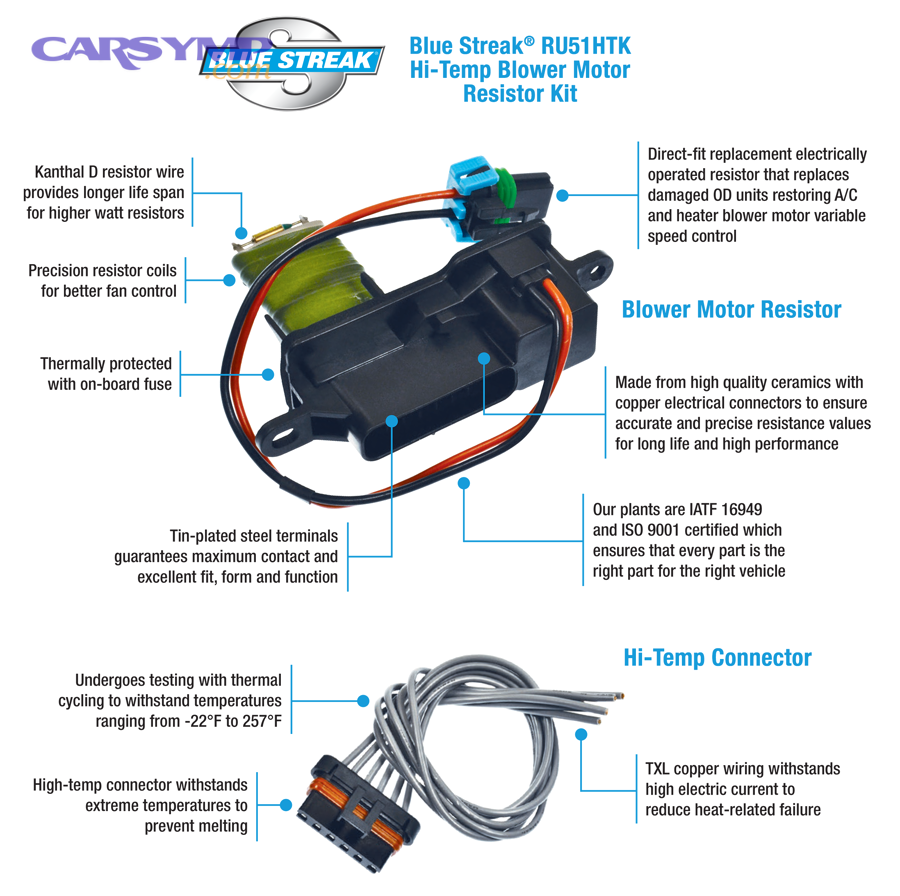

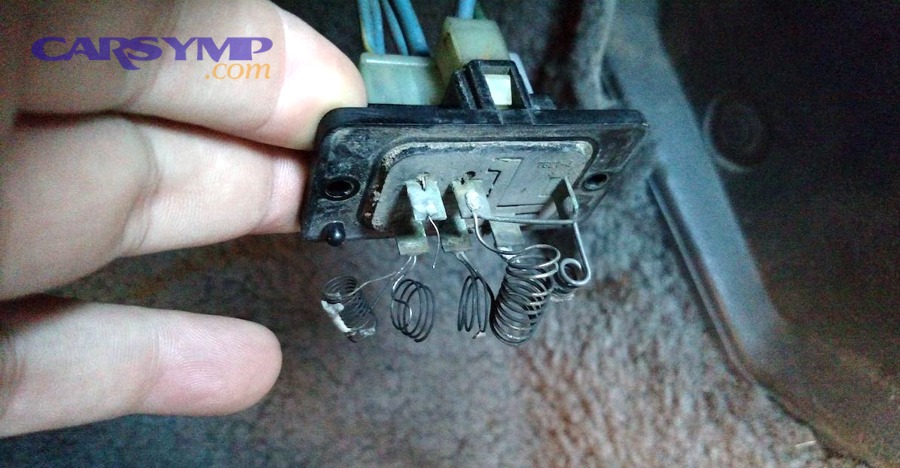

With the system powered off, an open resistor element or a visibly burned thermal fuse often confirms a resistor pack failure, but visual inspection alone is not enough if the connector pins are damaged. Next, you’ll inspect for burned coils, cracked solder joints, or a melted pigtail that creates intermittent contact.

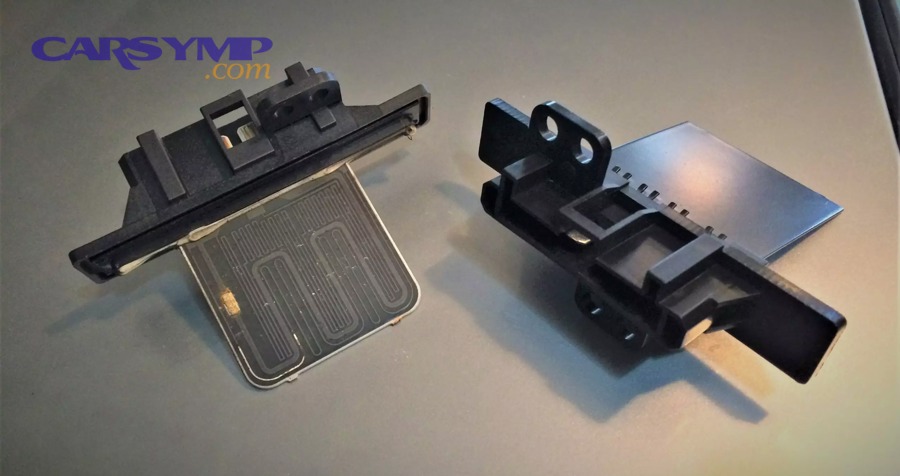

Many resistor packs show obvious heat damage: darkened coils, a melted plastic frame, or a blown thermal fuse. Solid-state blower control modules (common on automatic climate control) may not show obvious coil damage, but can still fail internally and require a functional voltage-output test.

Where does the blower resistor live, and why location matters for diagnosis?

The blower resistor/module is typically mounted in the HVAC air duct so airflow cools it; that location is itself a clue because low airflow can overheat the resistor and burn it out. Next, you’ll connect physical placement (in-duct cooling) to common failure chains like clogged filters or blocked ducts.

To start, look behind the glove box or near the blower motor housing. The resistor pack often bolts into the duct with a connector facing outward, while the motor mounts to the housing with a round flange.

Why low airflow can “cook” a resistor pack?

Because the resistor is cooled by passing air, restricted airflow raises its temperature and can trigger thermal protection or melt connectors over time. Next, you’ll check airflow health before installing a new resistor so the new one doesn’t fail again.

Restriction sources include a clogged cabin air filter, leaves packed around the blower wheel, or a stuck blend/recirculation door that reduces duct flow at the resistor location. If you replace a resistor without addressing airflow, the new part can overheat quickly—especially on lower speeds where resistor heat generation is higher.

What about automatic climate control systems with a “module” instead of resistors?

Automatic systems often use a transistorized blower control module that varies motor speed electronically, so failures can present as erratic speed control rather than missing steps. Next, you’ll treat “erratic ramps” and “no command response” as control-module clues and confirm by checking the control signal and module output.

In these systems, the HVAC control head sends a control signal to the module, and the module supplies a modulated output to the motor. If the signal is present but the output is missing or unstable, the module is suspect. If the signal is missing, the control head, sensor inputs, or wiring could be the root cause.

How do you tell airflow restriction from electrical failure?

Airflow restriction causes weak cabin airflow even when the motor audibly speeds up, while electrical failures cause missing speeds, cut-outs, or no motor sound despite a command. Next, you’ll combine “sound + feel + inspection” to prevent false diagnosis.

To begin, compare airflow at the vents on high versus low and listen: does motor pitch change normally? If pitch changes but airflow barely changes, suspect restriction or door issues.

How does cabin filter restriction mimic a weak blower?

A clogged cabin filter reduces airflow across all speeds, making the blower feel “weak,” and it can also increase resistor heat by reducing cooling airflow. Next, you’ll inspect and replace the cabin filter as a baseline step before condemning expensive parts.

Filters can clog with dust, pollen, and debris, especially in urban driving or heavy foliage areas. A severely restricted filter can make the blower motor work harder, raising current draw and heat at connectors. After installing a fresh filter, re-check airflow and fan noise; if performance returns, you avoided unnecessary part replacement.

Cabin filter impact on blower performance is often underestimated because the motor can still “sound busy” while actual airflow is choked. That mismatch is the key clue.

What debris problems create motor noise and imbalance?

Leaves, foam, and small objects can contact the squirrel cage, causing scraping sounds and vibration that mimic a failing motor bearing. Next, you’ll inspect the blower wheel and housing before buying a motor that might not be needed.

When debris sticks to the cage, the blower becomes unbalanced and may vibrate, leading to premature bearing wear. Cleaning the wheel and clearing the housing can restore smooth operation. If the bearing already has play or the wheel wobbles, then replacement becomes reasonable.

When weak airflow is actually a door or duct issue?

If airflow changes little between face/feet/defrost modes, or one side is consistently weak, the issue may be a stuck blend or mode door rather than the blower circuit. Next, you’ll check mode switching behavior and listen for actuator movement to separate “air routing” from “air generation.”

Door and actuator issues can create symptoms like strong airflow in defrost but weak in panel vents, or vice versa. That’s not a resistor signature; it’s an air routing signature. In those cases, electrical tests at the blower may be normal.

What are the most common root causes behind resistor and motor failures?

Resistors often fail from heat (restricted airflow, overheated connectors, high resistance), while motors often fail from wear (bearings, brushes) or contamination (debris, water intrusion). Next, you’ll connect each failure mode to a prevention step so the fix lasts.

To start, treat the blower circuit as a system: power delivery, control, airflow cooling, and mechanical load all interact.

Why connectors and pigtails fail along with the resistor?

High current plus slight terminal looseness creates heat, which oxidizes terminals and increases resistance, accelerating melt damage. Next, you’ll inspect pin tension and replace the pigtail if the connector shows discoloration or looseness.

Even if a new resistor is installed, a damaged connector can keep generating heat and kill the new part. That’s why many repair kits include a new pigtail harness. If you smell burning plastic or see softened connector housing, treat that as a root cause, not a side note.

How an over-amping blower motor can burn resistors and relays?

A blower motor with failing bearings can draw more current, heating the resistor/module and stressing relays and connectors. Next, you’ll measure current draw (if possible) or infer it from slow spin + hot wiring to decide whether the motor is the upstream cause.

When bearings drag, the motor requires more torque, increasing amperage. That extra heat can cook the resistor pack on lower speeds and can pit relay contacts on high speed. If a resistor has failed repeatedly, suspect the motor’s load and the airflow cooling path.

What role does water intrusion play?

Water intrusion can corrode motor bearings and connectors, leading to noise, intermittent operation, and voltage loss under load. Next, you’ll check for damp carpets, wet HVAC housing, or a clogged cowl drain that channels water toward the blower area.

Corrosion increases electrical resistance, which creates heat and intermittent contact. If you see green/white corrosion on terminals, the fix must include cleaning or replacing terminals—not only swapping parts.

How do you decide the correct repair path without replacing parts twice?

The correct path is: confirm symptom pattern, verify motor voltage on high, test low-speed output path, then check airflow and connector condition before ordering parts. Next, you’ll use a structured checklist so your decision is repeatable and not based on gut feel.

To begin, treat diagnosis as a comparison between “command,” “delivery,” and “response.” Command is the switch/controller. Delivery is wiring, relay, resistor/module. Response is motor spin and airflow.

Decision rules you can apply in under 30 minutes

If high works but one or more lower speeds don’t, the resistor/module path is primary; if voltage is present at the motor but the motor doesn’t spin, the motor is primary; if voltage is low on high, wiring/relay/ground is primary. Next, you’ll add connector inspection and airflow checks as tie-breakers.

- High works, low dead: resistor pack/module, resistor connector, or low-speed control signal.

- No speeds work, no motor sound: power supply (fuse/relay), ground, control head, or seized motor.

- All speeds weak + motor noisy: motor wear, debris contact, or airflow restriction.

- Intermittent + connector hot/melted: terminal resistance and pigtail replacement likely required.

Table-driven symptom mapping for faster diagnosis

This table contains common blower symptoms and what they most strongly indicate, helping you choose the next test instead of buying parts first.

It helps you translate “what you feel in the cabin” into “what you should measure at the connector.”

| Observed Symptom | Most Likely Cause | Best Next Check |

|---|---|---|

| Works only on high | Resistor pack/module path open | Check motor voltage on high vs low; inspect resistor connector |

| One or two lower speeds dead | Burned resistor element / failing module stage | Inspect resistor pack; verify low-speed output voltage |

| No speeds work; motor silent | Fuse/relay, ground, control issue, or seized motor | Check fuse/relay; test for voltage at motor on high |

| Blower squeals/grinds | Motor bearing wear or debris contact | Inspect blower wheel/housing; check for wobble and drag |

| Airflow weak at all speeds | Cabin filter/duct restriction or door issue | Inspect cabin filter and vents; verify mode door changes |

| Connector hot or melted | High resistance terminal + high current | Voltage drop test; replace pigtail connector as needed |

Practical prevention steps after the fix

Prevent repeat failure by restoring airflow, correcting connector resistance, and ensuring the motor load is normal, because heat is the common enemy in blower circuits. Next, you’ll verify post-repair function with a consistent, repeatable check.

- Replace/inspect the cabin filter and remove debris from the blower housing.

- Inspect and repair melted connectors; ensure pins are tight and clean.

- After replacing a resistor/module, verify all speeds operate and connectors remain cool after several minutes.

- After replacing a motor, verify smooth sound, stable current behavior (if measured), and strong airflow.

Contextual Border

Up to this point, you’ve diagnosed the core comparison: resistor vs motor vs wiring/control, using symptom mapping and targeted electrical checks. Next, you’ll expand into practical ownership decisions—what replacement involves, what it typically costs, and how to validate performance afterward—so the repair remains durable.

What should you consider before replacement and after the repair?

Before replacing parts, confirm the failure chain (airflow, connectors, current load), and after repair, validate speed control, airflow, and heat at connectors to ensure the fix is complete. Next, you’ll tie replacement choices to long-term reliability so you don’t redo the job.

What to know before a blower motor replacement?

blower motor replacement is justified when the motor has confirmed power/ground but won’t run, makes bearing noise, vibrates from internal wear, or draws excessive current. Next, you’ll check the blower wheel condition and connector integrity so the new motor isn’t installed into a failing electrical environment.

Because the blower is a high-current load, a weak connector or corroded ground can damage a new motor’s performance and heat the harness. Also, inspect the blower wheel: if it’s cracked or badly imbalanced, reuse can create vibration that shortens the new motor’s life.

When choosing a replacement, ensure the correct connector style and mounting pattern. If the old harness is heat-damaged, install the correct pigtail to restore proper terminal tension.

How cabin filter impact on blower performance affects your parts decision

A clogged cabin filter can make a healthy blower feel underpowered and can indirectly shorten resistor/module life by reducing cooling airflow, so filter inspection should be a first-line step. Next, you’ll use a “before/after filter” airflow comparison to verify whether restriction was the main problem.

If airflow improves dramatically after filter replacement and debris removal, you may not need a motor at all. If airflow remains weak but the motor pitch changes and electrical values are normal, consider air door/duct issues. If electrical output is missing on certain speeds, the resistor/module remains the likely culprit.

How to validate a blower motor replacement cost estimate intelligently

A Blower motor replacement cost estimate should reflect the motor type, accessibility (dash/footwell), and whether a connector pigtail or blower wheel is also needed. Next, you’ll compare estimates by labor steps rather than only the final number.

Ask whether the quote includes: debris cleanup, cabin filter replacement if restricted, and harness repair if the connector is heat-damaged. Also ask if the estimate includes diagnostic time or if diagnosis is separate.

Blower motor replacement cost estimate accuracy improves when the shop specifies the part brand/grade (OE-equivalent vs economy), warranty terms, and whether additional HVAC disassembly is required. If two quotes differ widely, compare labor hours and what’s bundled (motor only vs motor + wheel + pigtail + filter).

Post-repair checks that prove the diagnosis was correct

After the repair, verify all speeds, confirm smooth airflow increase across steps, and check that connectors stay cool, because these checks validate both the part and the underlying system health. Next, you’ll run a short “heat soak” test to catch marginal connections.

Run the blower on each speed for 30–60 seconds, then run high for several minutes. Feel for abnormal heat at the resistor/module connector and the motor connector (warm is suspicious; hot is unacceptable). Listen for scraping or vibration that suggests debris or a mis-seated wheel. Confirm that mode changes (panel/feet/defrost) work as expected, because weak routing can still make airflow “feel wrong” even with a new motor.

FAQ

Can a bad blower resistor drain the battery?

Usually no, but a shorted module or stuck relay can keep the blower circuit energized, which can drain a battery. Next, you’ll check whether the blower runs with the key off or whether a relay stays warm, because that points away from a simple open resistor and toward a control/relay fault.

Should you replace the resistor when doing blower motor replacement?

Not always, but it’s wise to inspect the resistor/module and its connector, especially if the old motor showed signs of high load or heat damage. Next, you’ll use connector condition and speed behavior as the deciding factor rather than replacing parts automatically.

Why does the blower work sometimes after hitting bumps?

This often indicates a loose connector, heat-damaged terminal tension, or worn motor brushes that regain contact when jolted. Next, you’ll confirm by gently moving the harness and monitoring voltage at the motor to separate “connection” from “internal motor” failure.

What if all speeds work but airflow is still weak?

If all speeds respond but airflow is weak, focus on restriction (filter, debris, ducts) and air doors rather than resistor or motor electrical failure. Next, you’ll inspect the cabin filter and blower wheel and confirm that mode doors direct air correctly.